Eighty-two years ago, on December 5, 1933, Amendment XXI to the US Constitution was ratified, repealing Amendment XVIII which had mandated nationwide Prohibition on alcohol on January 17, 1920. The Twenty-First Amendment is the only one of the 27 amendments of the U.S. Constitution to repeal a prior amendment. It is also unique as having been ratified by state ratifying conventions rather than by state legislatures.

The story of National Prohibition of alcohol and its ultimate repeal seems an historical oddity with little meaning for 21st Century life. Yet only recently in November 2012, voters in Colorado and Washington voted to legalize the production and sale of cannabis for social use, a first not only in the United States but also the world. Medical cannabis is now legal in twenty states and Washington, D.C., and many Americans use it in place of conventional pharmaceuticals. Nevertheless the federal government continues to raid and arrest people: 49.5 percent of all drug-related arrests involve the sale, manufacture, or possession of cannabis.

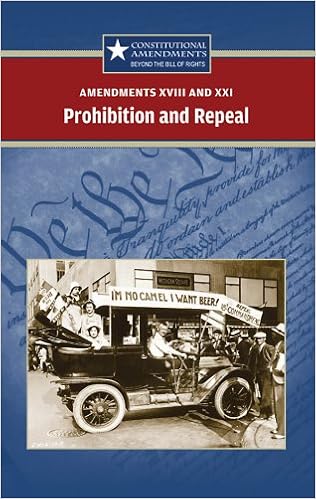

The story of alcohol prohibition under the Volstead Act is worth reviewing. Much of it is told in the Brooklyn Law Library’s copy of Amendments XVIII and XXI: Prohibition and Repeal by Sylvia Engdahl (Call # KF3919.A844 2009). Its 160 pages discuss the social and cultural forces that lead to Prohibition, the unintended consequences of the Eighteenth Amendment, the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment, and connections to the War on Drugs. National Prohibition was viewed by millions of Americans as the solution to the nation’s poverty, crime, violence, and other ills and they eagerly embraced it. After its adoption in 1920, Evangelist Billy Sunday staged a mock funeral for alcoholic beverages and then extolled on the benefits of prohibition. “The rein of tears is over,” he asserted. “The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs.” With the ban on alcohol which was seen as the cause of most, if not all, crime, some communities sold their jails.

The story of alcohol prohibition under the Volstead Act is worth reviewing. Much of it is told in the Brooklyn Law Library’s copy of Amendments XVIII and XXI: Prohibition and Repeal by Sylvia Engdahl (Call # KF3919.A844 2009). Its 160 pages discuss the social and cultural forces that lead to Prohibition, the unintended consequences of the Eighteenth Amendment, the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment, and connections to the War on Drugs. National Prohibition was viewed by millions of Americans as the solution to the nation’s poverty, crime, violence, and other ills and they eagerly embraced it. After its adoption in 1920, Evangelist Billy Sunday staged a mock funeral for alcoholic beverages and then extolled on the benefits of prohibition. “The rein of tears is over,” he asserted. “The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs.” With the ban on alcohol which was seen as the cause of most, if not all, crime, some communities sold their jails.

It soon became clear that Prohibition not only failed in its promises but actually created other serious and disturbing social problems leading to an increasing disillusionment by millions of Americans. Journalist H. L. Mencken wrote in 1925 that “Five years of prohibition have had, at least, this one benign effect: they have completely disposed of all the favorite arguments of the Prohibitionists. None of the great boons and usufructs that were to follow the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment has come to pass. There is not less drunkenness in the Republic but more. There is not less crime, but more. There is not less insanity, but more. The cost of government is not smaller, but vastly greater. Respect for law has not increased, but diminished.”

It was nine prominent New York lawyers, organized as the Voluntary Committee of Lawyers and chaired by eminent Park Avenue lawyer and Harvard Law School graduate Joseph H. Choate, Jr., who helped bring about Prohibition’s repeal. In 1927, the lawyers formed the VCL declaring as their purpose “to preserve the spirit of the Constitution of the United States [by] bringing about the repeal of the so-called Volstead Act and the Eighteenth Amendment.” With this modest platform they undertook first to draft and promote repeal resolutions for local and state bar associations. Their success culminated with the American Bar Association calling for repeal in 1928, after scores of city and state bar associations in all regions of the country had spoken unambiguously, in words and ideas cultivated, shaped, and sharpened by the VCL. For more on this remarkable story, see The VCL: Architects of Repeal by Richard M. Evans.