She was a young actress and model, new to New York City, who caught the attention of a wealthy and famous older man. After gaining the trust of her mother, the man lured the 16 year old alone to his apartment, plied her with champagne, and raped her after she had passed out. Despite this, she continued to have a relationship with him for a number of years, while he continued to support her family financially.

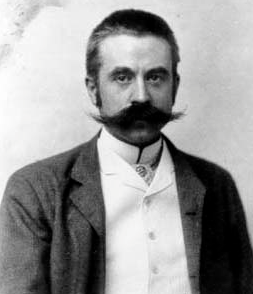

Some time later, she married another man, the heir to the fortune of a well-to-do Pittsburgh family. He had his own dark past: posing as a theatrical agent in New York, he had physically abused several young aspiring actresses. The women were all paid off to ensure their silence.

These events may sound all too familiar, especially in the wake of the #MeToo movement, but they occurred in the early 1900s and are the subject of Simon Baatz’s book The Girl on the Velvet Swing (Call No. HV 6534.N5 B33 2018). The young model was Evelyn Nesbit, the man who sexually assaulted her was renowned architect Stanford White, and her husband was Harry Thaw. Nesbit would become one of the first fashion icons, her image appearing in advertisements everywhere, but her prior entanglement with White would haunt her for her entire life. Things came to a head one sweltering night in 1906 when Thaw saw White in attendance at a performance in the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden. Yelling “You’ve ruined my wife,” he pulled out a pistol and shot White three times at close range. Stanny, as he was known to his friends, died instantly in a building of his own design (this second iteration of Madison Square Garden, erected in 1890, would be torn down in 1925.)

The story of Nesbit, White, and Thaw has been covered before in other books, including Nesbit’s autobiography from 1934, and Paula Uruburu’s American Eve (2008). What distinguishes The Girl in the Velvet Swing is the depth it gets into in describing the multiple trials and appeals, and the legal maneuvering undertaken by Thaw and his ever-changing legal team. How to defend the accused when he shot the victim in front of countless witnesses? Would the insanity defense fly if Thaw himself refused to assert it? How to take advantage of the system and free Thaw once he was committed to an asylum?

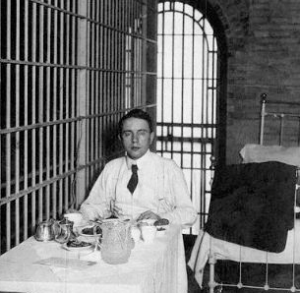

The book’s coverage of Thaw’s trial proceedings is full of rich detail, sourced from the many newspapers that were breathlessly reporting on the latest legal twists and turns: the New York World, New York American, New York Sun, among others (the Author’s Note at the end of the book provides further context as to the newspaper coverage.) Especially telling are the legal shenanigans that ensue after Thaw escapes from the Matteawan asylum in New York state. He lands in a small Quebec town across the border from Vermont, and his army of lawyers wage legal battle over extradition that spills over into the courts and politics of Canada.

When all was said and done, Harry Thaw had hired around 40 lawyers on his legal team, and had spent the staggering sum of $1 million on legal fees. And he was free. It’s another story that remains all too familiar to us today.

Towards the end, the book circles back to the putative center of the story, the girl who once innocently swung on Stanford White’s favorite apparatus, a velvet swing. But maybe the story was never really about Evelyn Nesbit. As she once lamented: “Stanny White was killed. But my fate was worse. I lived.”