The librarians from Brooklyn Law School are attending the 2018 conference of the American Association of Law Libraries in Baltimore, Maryland. We are honored to be part of an incredible profession with so many dedicated people willing to help law students, lawyers and legal professionals. Go to your library, speak with your librarians, educate yourself and don’t ignore the advantages that your librarians offer.

Take a look at some of the wonderful libraries listed in a new book from Taschen, Massimo Listri: The World’s Most Beautiful Libraries, withimages taken of the oldest libraries around the world, from medieval to 19th-Century institutions and private to monastic collections. It claims to be ‘a bibliophile beauty pageant’.

Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (The Vatican Library), Rome, Italy

The Vatican Library has its roots in the 4th Century CE, although in its current form it was established in the 15th Century. In the 16th Century Pope Sixtus V commissioned the architect Domenico Fontana to create new buildings to house the Vatican collections, and these are still used today. The decoration is so dizzyingly luxurious that it suggests a sort of fractal geometry. Like most of the vast Vatican complex, the library is a display of the spiritual and temporal influence that has allowed the Vatican to constitute itself as a sovereign state. In addition to documents spanning much of human history, the library possesses the oldest known manuscript of the Bible. When the librarian shushes you, you might want to listen: he has the rank of cardinal.

The Vatican Library has its roots in the 4th Century CE, although in its current form it was established in the 15th Century. In the 16th Century Pope Sixtus V commissioned the architect Domenico Fontana to create new buildings to house the Vatican collections, and these are still used today. The decoration is so dizzyingly luxurious that it suggests a sort of fractal geometry. Like most of the vast Vatican complex, the library is a display of the spiritual and temporal influence that has allowed the Vatican to constitute itself as a sovereign state. In addition to documents spanning much of human history, the library possesses the oldest known manuscript of the Bible. When the librarian shushes you, you might want to listen: he has the rank of cardinal.

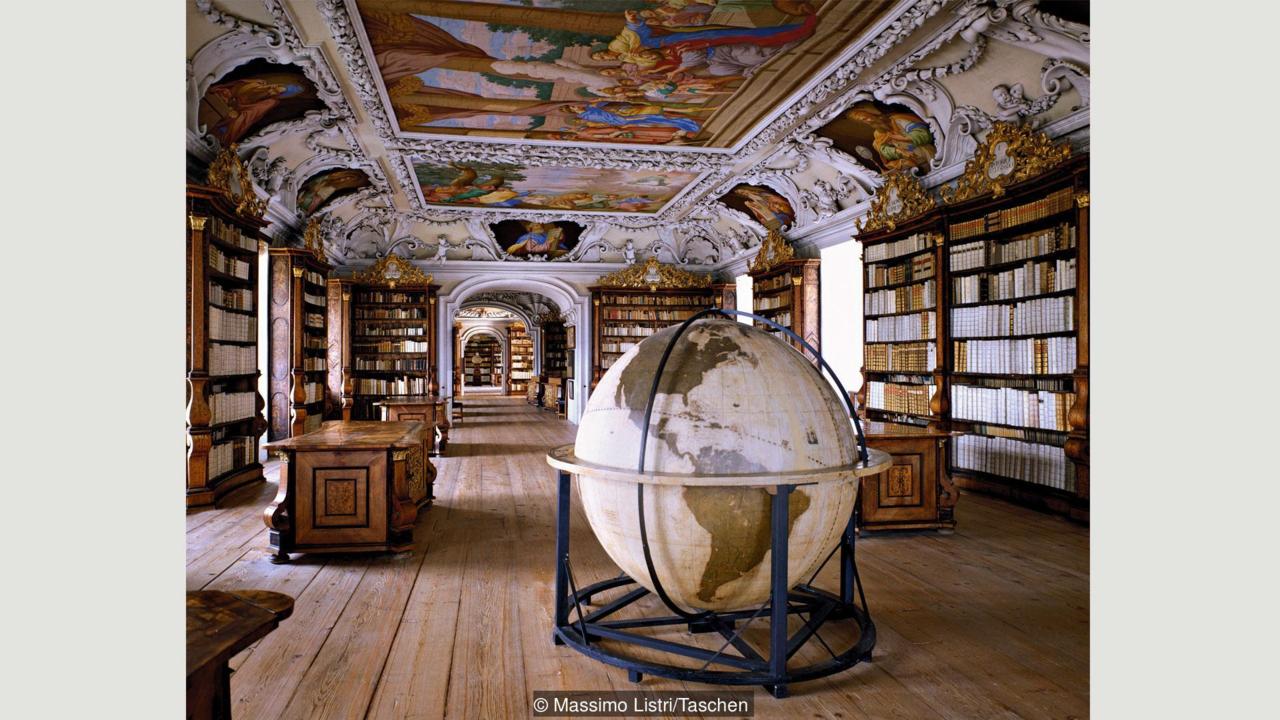

Stiftsbibliothek Kremsmünster (Kremsmünster Abbey Library), Austria

Kremsmünster Abbey was founded in 777 CE and its library holdings  include the Codex Millenarius, a famous 8th-Century manuscript of the Christian Gospels that depicts Saint Luke as a flying ox (Matthew, Mark, and John are a winged man, lion, and eagle respectively). Except for a raid in the 10th Century, after which repairs were made by Emperor Henry II, Kremsmünster for the most part escaped sacking, dissolution, and aristocratic expropriation; little wonder, since it sits on a hill like an intimidating fortress. Like many continental libraries, it was (re)built in the popular Baroque style in the 17th Century, according to which most surfaces (luckily not including the floor) are subjected to exuberant carving, gilding, and frescoes – although this library is positively restrained in comparison to some. Books as intellectual and cultural capital were once considered as valuable as jewels, and it made sense for them to be stored and displayed in gorgeous jewel boxes.

include the Codex Millenarius, a famous 8th-Century manuscript of the Christian Gospels that depicts Saint Luke as a flying ox (Matthew, Mark, and John are a winged man, lion, and eagle respectively). Except for a raid in the 10th Century, after which repairs were made by Emperor Henry II, Kremsmünster for the most part escaped sacking, dissolution, and aristocratic expropriation; little wonder, since it sits on a hill like an intimidating fortress. Like many continental libraries, it was (re)built in the popular Baroque style in the 17th Century, according to which most surfaces (luckily not including the floor) are subjected to exuberant carving, gilding, and frescoes – although this library is positively restrained in comparison to some. Books as intellectual and cultural capital were once considered as valuable as jewels, and it made sense for them to be stored and displayed in gorgeous jewel boxes.

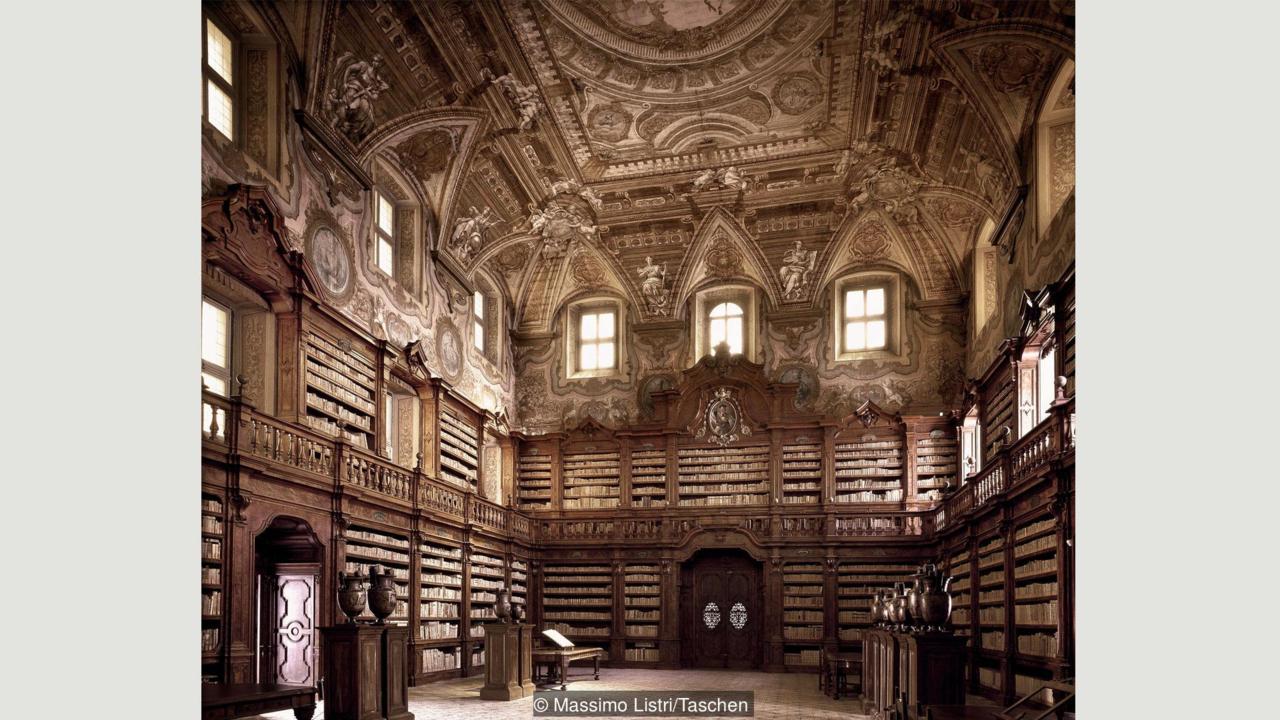

Biblioteca Statale Oratoriana dei Girolamini (The Girolamini Library), Naples, Italy The Girolamini library is part of a large complex founded by the  Oratorian religious order. The library hall is an imposing space that rises through three elegant stories: two levels of carved wood shelves, topped with late baroque plasterwork and frescoes. The sheer volume of books on display leaves one in no doubt that this is a place of higher study and research, as well as a warehouse of knowledge. Although it is wide ranging, the collection is particularly strong in music: the Oratorians believe in the importance of music and song in religious contemplation. This was the 18th-Century philosopher Giambattista Vico’s favourite library. It is also, sadly, an instance of a historic library being ransacked in the 21st Century: in 2012 it was discovered that a crime ring had been systematically looting and selling its valuable antique texts on the open market, although many of them have now been recovered. This episode is a valuable reminder, if one were needed, that humanity’s written heritage – the ‘memory of the world’, as Unesco calls it – remains under constant threat of attack.

Oratorian religious order. The library hall is an imposing space that rises through three elegant stories: two levels of carved wood shelves, topped with late baroque plasterwork and frescoes. The sheer volume of books on display leaves one in no doubt that this is a place of higher study and research, as well as a warehouse of knowledge. Although it is wide ranging, the collection is particularly strong in music: the Oratorians believe in the importance of music and song in religious contemplation. This was the 18th-Century philosopher Giambattista Vico’s favourite library. It is also, sadly, an instance of a historic library being ransacked in the 21st Century: in 2012 it was discovered that a crime ring had been systematically looting and selling its valuable antique texts on the open market, although many of them have now been recovered. This episode is a valuable reminder, if one were needed, that humanity’s written heritage – the ‘memory of the world’, as Unesco calls it – remains under constant threat of attack.

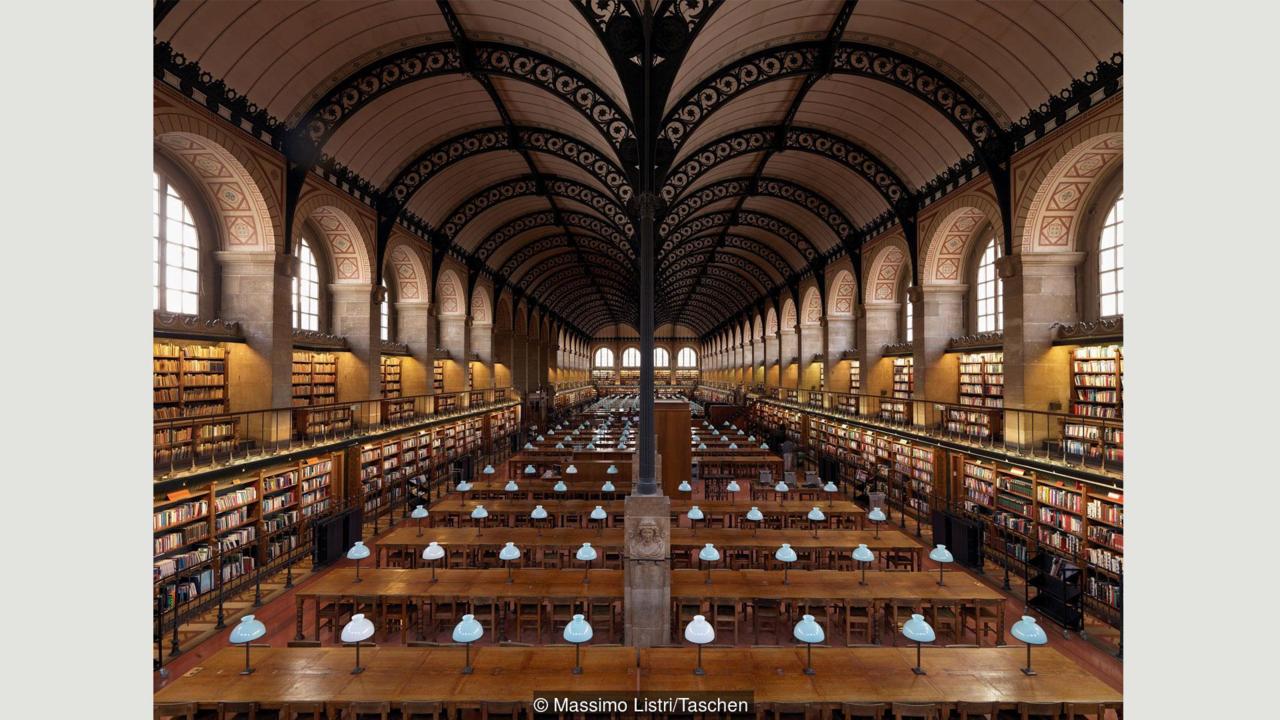

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (Sainte-Geneviève Library), Paris, France

Although we know it is probably older, documentary information about this library first appears in 1148. It was founded as a monastic library, survived the calamitous years of the Revolution intact (although the abbey it was a part of was dissolved and turned into a school), and now serves as the Paris Panthéon-Sorbonne university library. The library’s holdings expanded with the dissolution of other religious institutions and from confiscation of aristocratic collections. The new abbey church, built in the 18th Century, has been turned into the famous Panthéon, the national hall of fame. The current library building was created by the architect Henri Labrouste and opened in 1851. The majestic reading room is like an Industrial Age cathedral; the iron-frame construction brings to mind the other great public cathedrals of the period, the railway stations. In a modern arrangement, desks for readers are at centre stage, with the book stacks standing in graceful attendance. Gas lighting was employed in a monumental hall for the first time.

Although we know it is probably older, documentary information about this library first appears in 1148. It was founded as a monastic library, survived the calamitous years of the Revolution intact (although the abbey it was a part of was dissolved and turned into a school), and now serves as the Paris Panthéon-Sorbonne university library. The library’s holdings expanded with the dissolution of other religious institutions and from confiscation of aristocratic collections. The new abbey church, built in the 18th Century, has been turned into the famous Panthéon, the national hall of fame. The current library building was created by the architect Henri Labrouste and opened in 1851. The majestic reading room is like an Industrial Age cathedral; the iron-frame construction brings to mind the other great public cathedrals of the period, the railway stations. In a modern arrangement, desks for readers are at centre stage, with the book stacks standing in graceful attendance. Gas lighting was employed in a monumental hall for the first time.

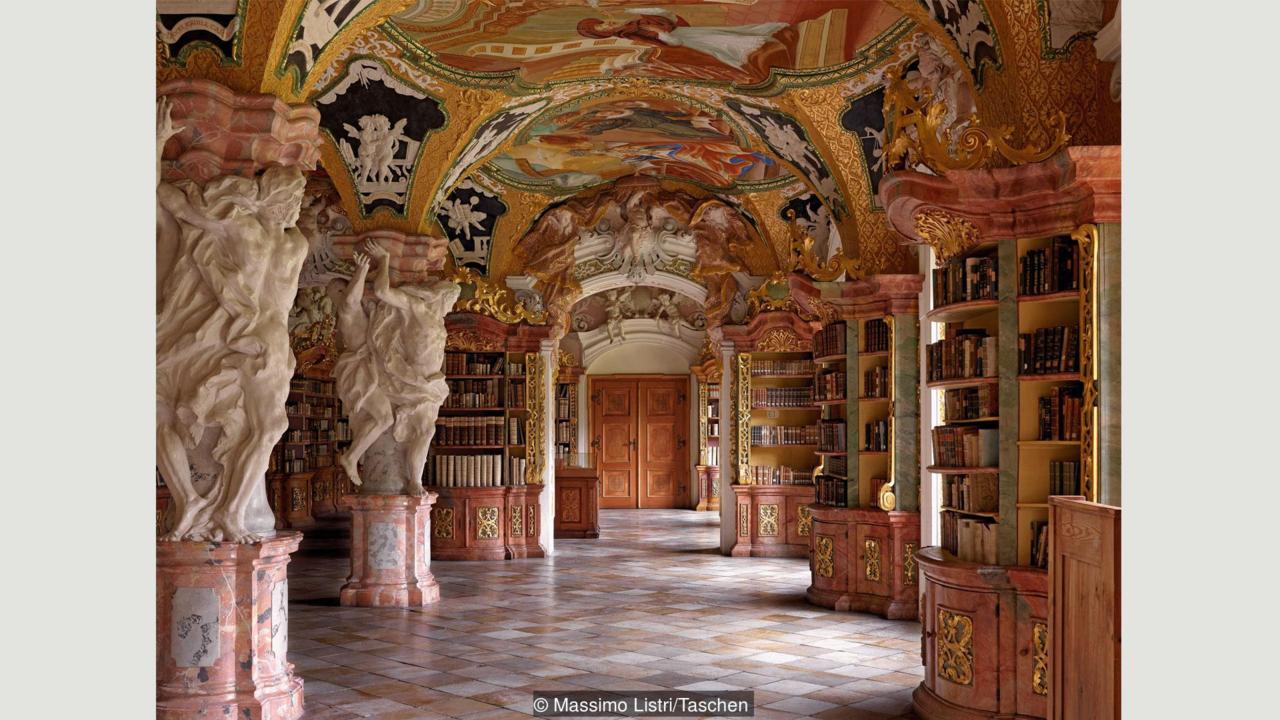

Klosterbibliothek Metten (Metten Abbey Library), Germany

The Benedictine Abbey at Metten was founded in 766 but was buffeted by the Reformation, war, social unrest, secularisation, and the realpolitik swirling around it. This reached a crescendo in 1803, when the abbey’s property, including its library holdings, were confiscated and auctioned off. However, under King Ludwig I of Bavaria the abbey was reopened and a new library was established; the site once more became a redoubt of knowledge and education. Under Abbot Märkl the monastery was transformed into a prelate’s palace, more in keeping with the prestige it commanded. Among its breathtaking official reception rooms are the library, which is designed along a sophisticated theological scheme. The result is a densely saturated and surprisingly playful palate of beautiful materials. The sculptor Franz Josef Holzinger was commissioned to create the ‘atlantes’ on the central columns to hold up the ceiling (because an ordinary marble column would never do). Christian heroes such as Thomas Aquinas are captured in scenes from their lives in the ceiling frescoes. If there is a problem with this Rococo approach to constructing a ‘temple of knowledge’, it is perhaps that one sometimes has to squint to find the books.

The Benedictine Abbey at Metten was founded in 766 but was buffeted by the Reformation, war, social unrest, secularisation, and the realpolitik swirling around it. This reached a crescendo in 1803, when the abbey’s property, including its library holdings, were confiscated and auctioned off. However, under King Ludwig I of Bavaria the abbey was reopened and a new library was established; the site once more became a redoubt of knowledge and education. Under Abbot Märkl the monastery was transformed into a prelate’s palace, more in keeping with the prestige it commanded. Among its breathtaking official reception rooms are the library, which is designed along a sophisticated theological scheme. The result is a densely saturated and surprisingly playful palate of beautiful materials. The sculptor Franz Josef Holzinger was commissioned to create the ‘atlantes’ on the central columns to hold up the ceiling (because an ordinary marble column would never do). Christian heroes such as Thomas Aquinas are captured in scenes from their lives in the ceiling frescoes. If there is a problem with this Rococo approach to constructing a ‘temple of knowledge’, it is perhaps that one sometimes has to squint to find the books.

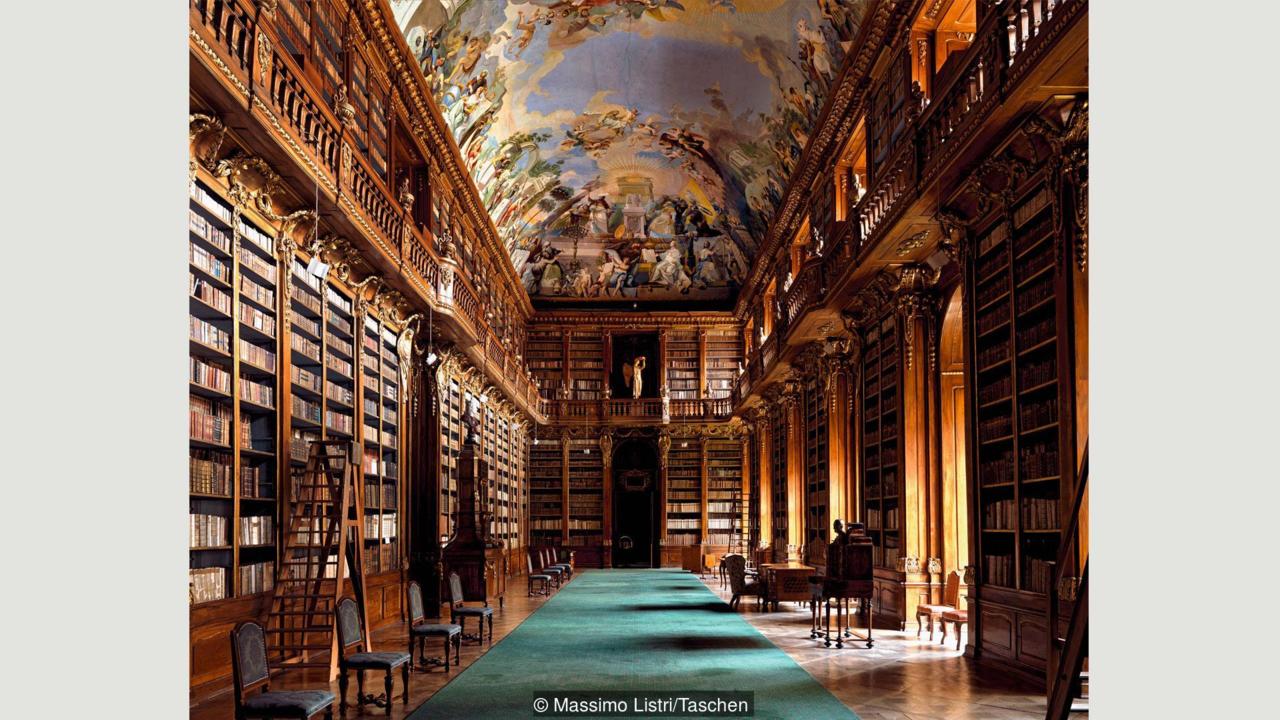

The Premonstratensian Strahov monastery was founded in 1143 and has  survived fire, wars, and plundering. Fortunately the holes torn in its collection have been more than made up for over the years by acquisitions and bequests. The library is home to the usual array of religious books, including the exquisite Strahov Evangeliary from the 9th Century, with semi-precious stones embedded in the binding, but its holdings cover a broad range of topics. In design, the library has two monumental halls. The Theological Hall was commissioned by the Abbot of Strahov in 1671; its riotous stucco work and many paintings and inscriptions (illustrating the principles of faith, study, knowledge, and divine providence) place it firmly in the Bohemian Baroque tradition. The fact that its codices are uniformly bound in white give the hall a pleasingly well-ordered feel. The Philosophical Hall (shown here) was built starting in 1783, is more neoclassical in design, and is characterised by its magnificent walnut book cabinets, which were salvaged from the dissolved abbey of Louka, in Moravia. After the Communist coup, the monastery was appropriated by the Czechoslovakian State in 1950 to become part of the Museum of Czech Literature. But after the fall of Communism, the collections were given back to the Premonstratensians, who have been working since to repair decades of neglect.

survived fire, wars, and plundering. Fortunately the holes torn in its collection have been more than made up for over the years by acquisitions and bequests. The library is home to the usual array of religious books, including the exquisite Strahov Evangeliary from the 9th Century, with semi-precious stones embedded in the binding, but its holdings cover a broad range of topics. In design, the library has two monumental halls. The Theological Hall was commissioned by the Abbot of Strahov in 1671; its riotous stucco work and many paintings and inscriptions (illustrating the principles of faith, study, knowledge, and divine providence) place it firmly in the Bohemian Baroque tradition. The fact that its codices are uniformly bound in white give the hall a pleasingly well-ordered feel. The Philosophical Hall (shown here) was built starting in 1783, is more neoclassical in design, and is characterised by its magnificent walnut book cabinets, which were salvaged from the dissolved abbey of Louka, in Moravia. After the Communist coup, the monastery was appropriated by the Czechoslovakian State in 1950 to become part of the Museum of Czech Literature. But after the fall of Communism, the collections were given back to the Premonstratensians, who have been working since to repair decades of neglect.

Stiftsbibliothek Sankt Gallen (Saint Gall Abbey Library), St Gallen, Switzerland For a long time, St Gall Abbey was one of the most important

intellectual centers in Western Europe, and it incorporates one of the largest medieval libraries in the world. The abbey was founded in the 7th Century by the Irish monk Gallus, and followed the Rule of St Benedict – the most bookish of saints, who required of his order the disciplined contemplation of religious texts – for more than a thousand years. A Greek inscription above the library’s entrance calls it a ‘sanctuary for the soul’. Today’s library arose during the Baroque remodelling of the abbey in the 18th Century by the architect Peter Thumb. The decoration befits a place of great cultural capital. There is rich, Rococo ornamentation everywhere, and especially in the stucco work. The carved wooden bookcases completely cover the walls on two levels, while the ceiling paintings depict ecumenical councils and church fathers. The abbey was added to the Unesco World Heritage list in 1983.

intellectual centers in Western Europe, and it incorporates one of the largest medieval libraries in the world. The abbey was founded in the 7th Century by the Irish monk Gallus, and followed the Rule of St Benedict – the most bookish of saints, who required of his order the disciplined contemplation of religious texts – for more than a thousand years. A Greek inscription above the library’s entrance calls it a ‘sanctuary for the soul’. Today’s library arose during the Baroque remodelling of the abbey in the 18th Century by the architect Peter Thumb. The decoration befits a place of great cultural capital. There is rich, Rococo ornamentation everywhere, and especially in the stucco work. The carved wooden bookcases completely cover the walls on two levels, while the ceiling paintings depict ecumenical councils and church fathers. The abbey was added to the Unesco World Heritage list in 1983.

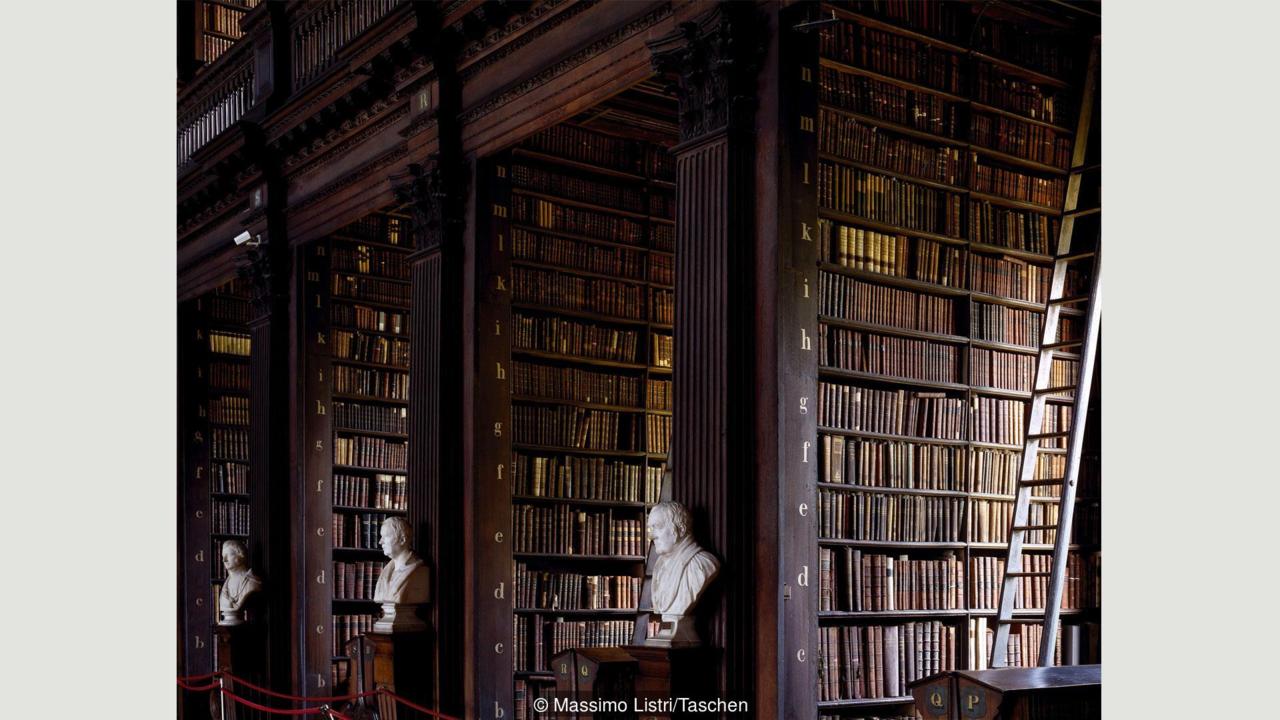

Trinity College Library, Dublin, Ireland PIf you still have your sunglasses on,  you can take them off now, because the Long Room at Trinity College Library is pleasingly low on ornamentation, and soothingly high on Enlightenment symmetries. Elizabeth I of England founded Trinity College in 1592 as a centre of Protestant scholarship, the idea being to break with the monastic tradition of learning and establish a new framework within the University of Dublin. Because the university outgrew its first library, a new building was planned by Thomas Burgh. Known as the Old Library, it was begun in 1712 and finished in 1732. It includes a spectacular 65m (215 ft)-long central space known as the Long Room; the original flat roof of the single-storey room was raised in 1858 and replaced with the oak barrel-vaulting that exists today. The Long Room’s oak shelves hold 200,000 of the university’s most valuable books. Among the intellectual worthies whose busts are ranked along the bookshelves are Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett, both of whom once used the library. (There are no women.) The library’s treasures include illuminated masterpieces such as the Book of Durrow (c 650–700) and the Book of Kells (c 800).

you can take them off now, because the Long Room at Trinity College Library is pleasingly low on ornamentation, and soothingly high on Enlightenment symmetries. Elizabeth I of England founded Trinity College in 1592 as a centre of Protestant scholarship, the idea being to break with the monastic tradition of learning and establish a new framework within the University of Dublin. Because the university outgrew its first library, a new building was planned by Thomas Burgh. Known as the Old Library, it was begun in 1712 and finished in 1732. It includes a spectacular 65m (215 ft)-long central space known as the Long Room; the original flat roof of the single-storey room was raised in 1858 and replaced with the oak barrel-vaulting that exists today. The Long Room’s oak shelves hold 200,000 of the university’s most valuable books. Among the intellectual worthies whose busts are ranked along the bookshelves are Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett, both of whom once used the library. (There are no women.) The library’s treasures include illuminated masterpieces such as the Book of Durrow (c 650–700) and the Book of Kells (c 800).