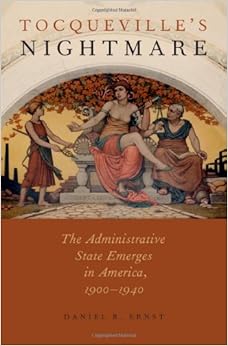

Brooklyn Law School Library latest New Books List has 70 items on a wide range of subjects. Of particular interest to legal scholars of administrative law is Tocqueville’s Nightmare: The Administrative State Emerges in America, 1900-1940 by Georgetown Law School Professor of Law Daniel R. Ernst (Call #JK411 .E76 2014). The subject may seem dry but Prof. Ernst, in less than 150 pages, tells a lively and compelling story of how legal giants from the early 20th (lawyers, judges and legal scholars such as Ernst Freund, Felix Frankfurter, Charles Evans Hughes, and Roscoe Pound) used the rule of law to respond to the problems posed by the growth of bureaucracy. Their combined efforts laid the foundations of American administrative law in the critical years between 1900 and 1940 culminating in the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act which codified already-established best practices.

Brooklyn Law School Library latest New Books List has 70 items on a wide range of subjects. Of particular interest to legal scholars of administrative law is Tocqueville’s Nightmare: The Administrative State Emerges in America, 1900-1940 by Georgetown Law School Professor of Law Daniel R. Ernst (Call #JK411 .E76 2014). The subject may seem dry but Prof. Ernst, in less than 150 pages, tells a lively and compelling story of how legal giants from the early 20th (lawyers, judges and legal scholars such as Ernst Freund, Felix Frankfurter, Charles Evans Hughes, and Roscoe Pound) used the rule of law to respond to the problems posed by the growth of bureaucracy. Their combined efforts laid the foundations of American administrative law in the critical years between 1900 and 1940 culminating in the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act which codified already-established best practices.

In the introduction, Ernst explains the title of his work recalling Alexis de Tocqueville’s visit to America in the 1830s and his observation that, while the United States had “centralized government”, it had little “centralized administration” or bureaucracies imposing their will on Americans. Tocqueville warned that if the United States ever became habituated to centralized administration “in that country a more insufferable despotism would prevail than any which now exists in the monarchical States of Europe, or indeed than any which could be found on this side of the confines of Asia.”

By 1940, America had acquired a great deal of centralized administration with administrators resolving disputes, collecting taxes, regulating industry, and distributing grants and loans. Proponents of the administrative state argued that the new agencies made individual freedom possible in an age of industrial concentration and national markets, in marked contrast to the dictatorships of Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin. Ernst suggests that the primary reason for the success of the American administrative experiment was Americans’ belief that courts would deliver them from Tocqueville’s nightmare. This gave a legalistic cast to the administrative state by applying the “rule of law” and ensuring that common-law courts would continue to serve as the ideal against which administrative agencies were judged. Agencies in their “quasi-adjudication” roles were bound by concepts of due process, were required to maintain judicial aloofness from subordinates, and were to justify their actions in deciding individual cases in legalistic ways: holding hearings, compiling a record of testimony, including detailed findings of facts supporting their orders. Many of these procedural safeguards came about from fear that America’s administrators would take their lead from political bosses and “professional office-seekers” who like European bureaucrats had little training and expertise and served partisan purposes.

In his concluding chapter, Ernst contrasts Elihu Vedder’s two murals in the Library of Congress, Corrupt Legislation and Good Administration: arresting depictions of the plight the creators of the American administrative state hoped to escape and the sound and just government they hoped to attain. In Good Administration, the central female figure is chastely robed and serene. The scales she holds are in equipoise and on her shield are emblems of a just government, the weight, scales, and rule. To her left, a young man drops a ballot into a voting urn. On the right, a young woman winnows wheat over another voting urn. Behind them is a thriving wheat field. In contrast, the central figure in Corrupt Legislation is a woman with a beautiful but depraved face. The path to her thrown is overgrown with w

In his concluding chapter, Ernst contrasts Elihu Vedder’s two murals in the Library of Congress, Corrupt Legislation and Good Administration: arresting depictions of the plight the creators of the American administrative state hoped to escape and the sound and just government they hoped to attain. In Good Administration, the central female figure is chastely robed and serene. The scales she holds are in equipoise and on her shield are emblems of a just government, the weight, scales, and rule. To her left, a young man drops a ballot into a voting urn. On the right, a young woman winnows wheat over another voting urn. Behind them is a thriving wheat field. In contrast, the central figure in Corrupt Legislation is a woman with a beautiful but depraved face. The path to her thrown is overgrown with w eeds, showing that people have abandoned a direct approach to Justice. In her left hand the woman holds a set of scales onto which a man is placing a sack of coins as his bribe. In the background is the man’s factory, smoke billowing from its stacks. Another factory to the woman’s right is still and in disrepair. A poorly clad girl, representing Labor, appeals to the woman for employment but is waved away.

eeds, showing that people have abandoned a direct approach to Justice. In her left hand the woman holds a set of scales onto which a man is placing a sack of coins as his bribe. In the background is the man’s factory, smoke billowing from its stacks. Another factory to the woman’s right is still and in disrepair. A poorly clad girl, representing Labor, appeals to the woman for employment but is waved away.

If the early 20th Century father of the administrative state expected to avoid Tocqueville’s nightmare, they knew that administrators would not stay good on their own, and they designed the administrative state accordingly. The emergence of a procedural rule of law during the heyday administrative adjudication remains relevant as the various methods of holding administrators accountable tried out before 1940 are part of a repertoire that we still turn to today. Ernst’s history shows that we can have an administrative state without transgressing fundamental principles of American governance.

Another new item in the BLS Library collection takes a different view of the subject. Is Administrative Law Unlawful? by Columbia Law School Professor of Law Philip Hamburger (Call # K3400 .H253 2014) has more than 635 pages which suggests only an affirmative response is correct for the question in the title. In his review of the book, Harvard Law School’s Adrian Vermeule says otherwise seeing praise of this book “as a sign of the times, a portent of the dimming of the legal mind, that this book is described in some quarters as ‘brilliant’ and ‘path-breaking.’ It isn’t; and the only sensible response to Hamburger’s question, as far as I can see, is ‘no.’ He calls the book a “dark vision of lawless and unchecked power” in which the author “wants us to see that American administrative law is ‘unlawful’ root-and-branch, indeed that it is tyrannous — that we have recreated, in another guise, the world of executive ‘prerogative’ that would have obtained if James II had prevailed, and the Glorious Revolution never occurred. The administrative state stands outside, and above, the law. . . . There is too much in this book about Charles I and Chief Justice Coke, about the High Commission and the dispensing power. There is not enough about the Administrative Procedure Act, about administrative law judges, about the statutes, cases and arguments that rank beginners in the subject are expected to learn and know. The book makes crippling mistakes about the administrative law of the United States; it misunderstands what that body of law actually holds and how it actually works. As a result the legal critique, launched by five-hundred-odd pages of text, falls well wide of the target.”

Another new item in the BLS Library collection takes a different view of the subject. Is Administrative Law Unlawful? by Columbia Law School Professor of Law Philip Hamburger (Call # K3400 .H253 2014) has more than 635 pages which suggests only an affirmative response is correct for the question in the title. In his review of the book, Harvard Law School’s Adrian Vermeule says otherwise seeing praise of this book “as a sign of the times, a portent of the dimming of the legal mind, that this book is described in some quarters as ‘brilliant’ and ‘path-breaking.’ It isn’t; and the only sensible response to Hamburger’s question, as far as I can see, is ‘no.’ He calls the book a “dark vision of lawless and unchecked power” in which the author “wants us to see that American administrative law is ‘unlawful’ root-and-branch, indeed that it is tyrannous — that we have recreated, in another guise, the world of executive ‘prerogative’ that would have obtained if James II had prevailed, and the Glorious Revolution never occurred. The administrative state stands outside, and above, the law. . . . There is too much in this book about Charles I and Chief Justice Coke, about the High Commission and the dispensing power. There is not enough about the Administrative Procedure Act, about administrative law judges, about the statutes, cases and arguments that rank beginners in the subject are expected to learn and know. The book makes crippling mistakes about the administrative law of the United States; it misunderstands what that body of law actually holds and how it actually works. As a result the legal critique, launched by five-hundred-odd pages of text, falls well wide of the target.”

Christopher Beauchamp speaks about his first book, Invented by Law: Alexander Graham Bell and the Patent That Changed America (Call# KF 3116.B43 2015). Published by Harvard University Press, the book explores questions of ownership and legal power raised by the invention of the telephone, and tells of a forgotten history with wide relevance for today’s patent crisis. Using the invention of the telephone in 1876 as one of the great touchstones of American technological achievement, Beauchamp sheds new light on that history, and examines the legal battles that raged over Bell’s telephone patent, perhaps the most consequential patent right ever granted. Prof. Beauchamp shows that the telephone was as much a creation of American law as of scientific innovation.

Christopher Beauchamp speaks about his first book, Invented by Law: Alexander Graham Bell and the Patent That Changed America (Call# KF 3116.B43 2015). Published by Harvard University Press, the book explores questions of ownership and legal power raised by the invention of the telephone, and tells of a forgotten history with wide relevance for today’s patent crisis. Using the invention of the telephone in 1876 as one of the great touchstones of American technological achievement, Beauchamp sheds new light on that history, and examines the legal battles that raged over Bell’s telephone patent, perhaps the most consequential patent right ever granted. Prof. Beauchamp shows that the telephone was as much a creation of American law as of scientific innovation.

The Brooklyn Law School Library New Books List for January 14, 2015 includes 88 items recently added to the collection. Among them is

The Brooklyn Law School Library New Books List for January 14, 2015 includes 88 items recently added to the collection. Among them is  The BLS Library has a number of titles in its collection on the subject of grand juries including

The BLS Library has a number of titles in its collection on the subject of grand juries including  Students at Brooklyn Law School are focused on their upcoming exams. Soon enough they will be in the legal work force and will need to exercise best practices in records management. The BLS Library has in its most recent

Students at Brooklyn Law School are focused on their upcoming exams. Soon enough they will be in the legal work force and will need to exercise best practices in records management. The BLS Library has in its most recent

The BLS Library recently added to its collection an E-book titled

The BLS Library recently added to its collection an E-book titled  It is based on the book

It is based on the book  Brooklyn Law School Library latest

Brooklyn Law School Library latest  In his concluding chapter, Ernst contrasts Elihu Vedder’s two murals in the Library of Congress, Corrupt Legislation and Good Administration: arresting depictions of the plight the creators of the American administrative state hoped to escape and the sound and just government they hoped to attain. In Good Administration, the central female figure is chastely robed and serene. The scales she holds are in equipoise and on her shield are emblems of a just government, the weight, scales, and rule. To her left, a young man drops a ballot into a voting urn. On the right, a young woman winnows wheat over another voting urn. Behind them is a thriving wheat field. In contrast, the central figure in Corrupt Legislation is a woman with a beautiful but depraved face. The path to her thrown is overgrown with w

In his concluding chapter, Ernst contrasts Elihu Vedder’s two murals in the Library of Congress, Corrupt Legislation and Good Administration: arresting depictions of the plight the creators of the American administrative state hoped to escape and the sound and just government they hoped to attain. In Good Administration, the central female figure is chastely robed and serene. The scales she holds are in equipoise and on her shield are emblems of a just government, the weight, scales, and rule. To her left, a young man drops a ballot into a voting urn. On the right, a young woman winnows wheat over another voting urn. Behind them is a thriving wheat field. In contrast, the central figure in Corrupt Legislation is a woman with a beautiful but depraved face. The path to her thrown is overgrown with w eeds, showing that people have abandoned a direct approach to Justice. In her left hand the woman holds a set of scales onto which a man is placing a sack of coins as his bribe. In the background is the man’s factory, smoke billowing from its stacks. Another factory to the woman’s right is still and in disrepair. A poorly clad girl, representing Labor, appeals to the woman for employment but is waved away.

eeds, showing that people have abandoned a direct approach to Justice. In her left hand the woman holds a set of scales onto which a man is placing a sack of coins as his bribe. In the background is the man’s factory, smoke billowing from its stacks. Another factory to the woman’s right is still and in disrepair. A poorly clad girl, representing Labor, appeals to the woman for employment but is waved away. Another new item in the BLS Library collection takes a different view of the subject.

Another new item in the BLS Library collection takes a different view of the subject.  The BLS Library Law Library has an extensive collection of books on the Constitution, its history and interpretation. To locate books on the history of the Constitution, use the SARA catalog to conduct a subject search using the phrase: United States — Constitutional history. Some recent acquisitions in the BLS Library collection include

The BLS Library Law Library has an extensive collection of books on the Constitution, its history and interpretation. To locate books on the history of the Constitution, use the SARA catalog to conduct a subject search using the phrase: United States — Constitutional history. Some recent acquisitions in the BLS Library collection include  Another recent acquisition to the BLS Library collection on the subject is

Another recent acquisition to the BLS Library collection on the subject is